A Short History of the Burren

MESOLITHIC - c. 7000 - 4000 BC

The oldest evidence of mankind in Ireland dates from the Palaeolithic/Old Stone Age, circa 12.500 years to 9,000 years ago. However, no evidence of Palaeolithic mankind has been found in the Burren.

The oldest evidence of mankind in the Burren was actually found in recent times at a midden, (rubbish pile), site near Fanore beach in the north-west of the Burren. The finds have been dated to more than 6,000 years ago and are thus from the Mesolithic/Middle Stone Age. The Mesolithic people practiced the hunting and gathering tradition just like their predecessors in the Palaeolithic. However, the Mesolithic stone tools were more sophisticated than those of the Palaeolithic people. The Mesolithic in Ireland dates from circa 9,000 to 6,000 years ago.

The Mesolithic communities would have concentrated settlement on the Burren coast and river valleys. The landscape would have consisted of a dense cover of oak in the valleys and a mosaic of limestone pavement and hazel/pine in the uplands. These pre-farming peoples with their low-impact living model would have had little impact upon the forest cover.

NEOLITHIC - c. 4000 - 2400 BC

All was to change however when the first farmers arrived into the Burren, (and Ireland), about 6,000 years ago. This New Stone Age, (Neolithic), marked a radical cultural shift in the story of mankind here. The new immigrant communities introduced megalithic culture – the custom of placing the remains of special dead communally in big stone structures. The most ancient megalithic structure thus far dated in Ireland is the Poulnabrone portal tomb in the Burren. It is one of the most significant icons of prehistoric Ireland. The oldest bones in the tomb have been dated to 5,800 years ago.

These pioneer farmers used polished stone axes and elected to slash and burn the lighter wood in the Burren hills i.e. the hazel and pine. No surprise then that all of the prehistoric tombs in the Burren are concentrated on the limestone pavement areas. The fertile valleys with their thick cover of glacial drift were covered in virgin oak forest for most of the Burren prehistoric period.

BRONZE AGE - c. 2000 - 600 BC

Farming carried on relentlessly in the Burren in the successive Bronze Age. The mortuary tradition changed however from communal burial in the megaliths to the custom of individual burial. The dead were interred in stone chambers or boxes which were often covered with a huge aggregate of loose stones (cairns). Many of the cairns in the Burren are located on the summits of hills – locations which must have had a lot of spiritual significance for the communities.

The cumulative effect of slashing/burning, exuberant farming and climate change about 3,000 years ago was the erosion of substantial amounts of soil. Thus the Burren’s highly distinctive limestone pavement areas today have been caused by two separate phenomena – glacial erosion and prehistoric agri-vandalism.

IRON AGE c . 600 BC - 400 AD

The Iron Age remains enigmatic in the Burren and Ireland as it is characterised by a mysterious lull in farming and a regeneration of forest.

EARLY MEDIEVAL c. 400 - late twelfth c. AD

Christianity probably arrived in to the region in the 5th century – the period in which the religion reached Ireland. The period from the 5th century to the end of the 12th century is known as the Early Medieval. The story of man and the Burren landscape took a dramatic turn as settlement and farming activity shifted from the eroded hills to the fertile valleys. The oak was removed to facilitate the mixed farming economy of livestock and cereal production.

The robustness of the farming economy is reflected in the very rich archaeological legacy from this period. The Burren is home today to a whopping 450 ring forts – the fortified farmsteads of the Early Medieval élite. The religious equivalent of the fort was the monastic site. Esteemed archaeologist, John Sheehan, reckons there are up to 30 Early Medieval ecclesiastical sites in the Burren – one of the highest concentrations in Ireland.

MEDIEVAL late twelfth c. - early sixteenth century c. AD

The real revolution in the Burren in the Medieval period was not political but religious. County Clare was ringed by Anglo-Norman colonists but areas in the county such as the Burren remained under the control of the indigenous Gaelic élite. However, the religion was mainstreamed from the idiosyncratic Irish take on Christianity to orthodox Roman discipline. This “globalisation” is reflected still today physically in the Burren landscape by the abbeys and parish churches constructed by European orders (Augustinians, Cistercians…) in continental architectural styles – Romanesque and Gothic. Meanwhile, the lay Gaelic élite were following the national trend of abandoning the ring forts for tower houses. The latter were more practical for defence and dwelling purposes. More than half of the 21 tower houses in the region are located at critical entry/exit points – strong evidence of the Burren’s importance as a farming region.

POST MEDIEVAL early 16th c. AD - 1850

The two most important historical events in the Burren in post-medieval times were the Cromwellian plantations and the Great Hunger. The Cromwellian wars took place in Ireland in the 1640s. One of the results of the wars was that large swathes of the west of Ireland finally came under British dominion. The land of the Gaelic élite was expropriated and assumed by Cromwellian adventurers. The ruins of tower houses in the Burren are emblems of the demise of the kingdoms of Gaelic élites such as the O’Briens and the O Lochlans.

Interestingly sheep farming seemed to become extensive in the Burren uplands following the 17th century plantations. However, the vast majority of human settlement remained in the valleys. By Famine times, there were up to 400 people per square mile living in several Burren valleys. The Great Hunger affected County Clare more than any other county in Ireland apart from Mayo. 85% of the people in the Burren were living in housing of 4th classification according to the census of 1841. The population of County Clare is more than 50% less now than what it was pre-Famine (261,000 then). The physical evidence of the famine in the landscape is widespread still today in the form of Famine relief roads, abandoned potato cultivation ridges (“lazy beds”), Famine workhouses and isolated ruins of pre-Famine dwellings and villages. Most of the peasantry at the time lived in mud cabins which have perished.

TODAY

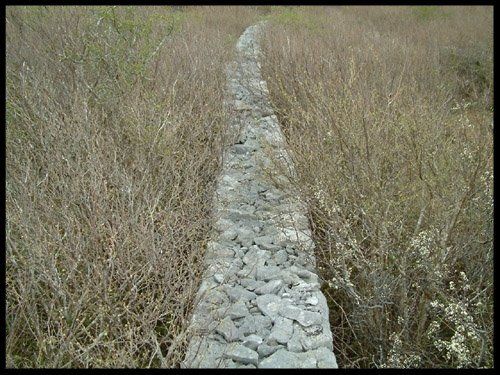

The pressure on the Burren uplands for food and fuel was unsustainable in pre-Famine times. It is a rich irony that the thinking now is that there is not enough pressure on the Burren hills i.e. that the decline of winter farming in recent decades has led to scrub overwhelming much of the limestone pavement, archaeology and Burren speciality wild flowers. The people and landscape narrative in the region has flipped in the space of less than 200 years.