St Patrick's Well, Rossalia

LOCATION

The well is located in a small cliff face in the townland of Rossalia on the north eastern slope of Abbey

hill. It is 4 kilometres south east of New Quay and 11 kilometres west of Kinvara, Co

Galway. An impermeable chert-rich

zone on the limestone slope has caused a small outflow of water. The initial part of the outflow was walled in with a well

house and is known as Tobar Phádraig (St Patrick’s Well).

An old, unsurfaced road (known as a “green road”) lies just below the well. Less than one kilometre to the east of the well, the green road links up with an ancient North Clare route way i.e. Carcair na gCléireach (literally the Clerics’ Slope), commonly known as the Corker Pass. This route from north Clare into south Galway dates back to the 16th century at least (Gosling 1991, 126). Thus, St Patrick’s has enjoyed a strategic location for centuries at least.

Furthermore, holy wells are often site-specific for symbolic reasons.

Some are located on the sea shore (O’Sullivan/Dowling 2006, 37). Though St

Patrick’s is not on the seashore, its expansive sea views means that the well

enjoys a liminal land/water, world/otherworld location.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gosling, P. (2001). The Burren in Medieval Times. The Book of the Burren

. 2nd

edition. Kinvara ; Tír Eolas.

O’Sullivan M. Downey L. (2006). Know Your

Monuments Holy Wells. Archaeology

Ireland.

Spring Edition.

Dublin –

Wordwell Books.

FOLK RELIGION

The folk interpretation of the

outflow of water is much more colourful that the scientific one! The story goes that a woman was

fainting from dehydration as she was walking up Abbey Hill. She sat down on a

rock and started to cry as her attempts to find water had failed. Suddenly, St. Patrick approached her and asked her why she was crying. The woman

explained her situation. St. Patrick knelt down beside a rock and prayed to God

that a well would spring up. It duly did. St. Patrick then blessed the well. (IFC 1937, 0049, 0169). Thus the miraculous powers of the well are attributed to the saint.

As the well was believed to be sacred and suprenatural, local people did not believe that the water would boil. Moreover, they would not dare to try to boil the water as they feared they might invoke the displeasure of St Patrick.

People who were suffering from pain in their limbs visited the well for the

cure. They washed the affected part with the holy water. They would also take

home some of the water in a bottle so that they could rub their limbs in the

event of the pain recurring (IFC 1937, 0049, 0170).

Holy wells renowned for cure for sore limbs are uncommon. In

an inventory of 43 wells in North Clare, the cures were documented for 25 of

them. Only one of the 25 wells was renowned for sore limbs – Toberadubh,

Caherfadda (Doolin 1991, 168-169).

The patron feast day at the Rossalia well is March 17th, St Patrick’s Day. (IFC 1937, 0049, 0170). Patrick's patron day falls on this date as it is reputed to be his date of death. It was not essential to visit holy wells on the patron day in order to get the cure. However, there are traditions of the water being most effective on that day (Ó Giolláin 2005, 16).

Offerings recorded at the well in the 1840s were “rags, pins, and other worthless offerings of devotees”. They were deposited in a niche within the well house. Talismanic stones were also noted on site – “large, but rudely shaped stones, ranged apparently in religious order” (Cooke 1842-43).

By the 20th century, the votive offerings included “turnips, prayer books, beads, medals and stones”. (IFC 0049, 0170).

Talismanic stones are also recorded at other North Clare holy wells including Tobermacduagh, Keelhilla , Bullán Phádraig, Poulnalour and Tober Moon, Kilmoon West (Westropp 2003,36). “The veneration of stones is often a part of the ritual carried out during pilgrimages to holy wells” (Logan 1980, 97). The stones (often curiously shaped) are imbued with special powers and include swearing stones, cursing stones, returning stones, floating stones and holed stones (Logan 1980, 97-120).

A tiny number of offerings and a photograph of a young

person were noted in the well niche in February 2020.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Irish Folklore Commission, The

Schools’ Collection (1937). Dublin.

O’Connell J.W. and A. Korff (2001) Lores and Cures and Blessed Wells Lelia

Doolin. The Book of the Burren

. 2nd Edition.

Kinvara – Tír

Eolas.

Ó Giolláin, D. (2005).

Revisiting the Holy Well. Éire-Ireland.

1 & 2. Spr/Sum 05. Éire-Ireland. New Jersey – Irish American Cultural

Institute.

Cooke, Thomas L.

(1842-43) . Autumnal Rambles about New Quay, County Clare.

Galway -

Galway

Vindicator.

Comber, M (ed.) (2003). Folklore of Clare T.J.Westropp.

Ennis –

Clasp Press.

Logan, P. (1980). The Holy Wells of

Ireland.

Buckinghamshire - Colin Smythe.

THE COMYN CENOTAPH

A cenotaph is a memorial monument to someone who is buried elsewhere. The Comyn cenotaph is located about 30 metres north west of the holy well. It is a

rectangular stone mortared structure (L 1.6m ; Wth 1.5m ; H 1.6m). It has been variously described as “a pillar” (Cooke 1842-43), “a memorial

stone” (Coffey 1995, 16-17 ),”

an

erection ”

(Beresford Massy 1902, Vol V (2)

and a leacht cuimhne

(Tunney

2016) . Leacht cuimhne

translates as

memorial stone. There is an etched tablet in the cenotaph as well as a decorated stone. The tablet reads as follows -

LORD JHSUS

CHRIST HAV

MERCY ON

US PRAY FOR

THE SOULES

OF JOHN COR

NYM AND HIS

WIFE MARY

MNEMARA 1765

The text is in conjoined letters and they are laid out poorly with words spilling from one line on to the next. The disorderly script is explained by the fact that the masons who were inscribing the slabs in those times were illiterate and were copying something they could not read (Jones 2004, 229). It is also worth noting that spelling of names was more variable back then than it is today.

The inscribed "John Cornym" and "Mary M Nemara" would read as John Comyn and Mary Mc Namara. The fourth digit is indistinct but the date appears to us to be 1765. This may be the year of death of one of the couple or both.

The decorated stone consists of a moon face, a symbol of death. It had been partnered by another stone with a sun face on it, a symbol of life. The latter stone was re-located from a decaying side of the cenotaph and was used in the construction of the well house (Coffey 1995, 16-17). The twin stones of sun and moon would have represented the life and death of the Comyns. The moon face is better known today as the logo of local landscape charity, Burren Beo.

The monument may have been commissioned by their son Peter Comyn (1778-1830).Peter was a magistrate who led a colourful and turbulent life. He was found guilty of arson, perjury and forgery and was hung at 52 years of age. Though he was a member of the landlord class, Comyn had a strong interest in the folk customs of the tenantry. A manuscript was found posthumously in which he documented local legends and “the habits, morals and superstitions of the primitive and sequestered people among whom he lived” (O’Donovan and Curry 1839, 11). It is thus not altogether surprising that he located the memorial at the site of St Patrick’s well - a local centre of folk religion then. Comyn also probably choose this location as it was a busy thoroughfare in an area of outstanding natural beauty.

The

monument’s condition was decried as far back as the mid-1800s, being described

as “mutilated” with vegetation growing out of it

(Cooke 1842-43). It was

depicted as “sadly crumbling away slowly” as recently as the 1970s (Coffey

1995, 16-17). The monument has been re-pointed and cemented since then and is

happily now in good condition.

Some

commentators have defined the mound around the monument as a fulachta fia

(prehistoric burned mound) .

However, the most recent

archaeological view is that the mound is spoil (Tunney). The spoil probably

consists of waste material drawn up during the digging of the foundations for

the monument.

19th century cenotaphs are quite rare in

County Clare. However, there are 28 examples of such monuments on Inis Mór,

dating from 1811 to 1876.

They

differ diagnostically from the Comyn monument in that they are “higher than a

man” and are surmounted by a cross. Furthermore, the Inis Mór complex commemorate

ordinary islanders whereas the Comyn monument perpetuates the memory of members of the landed gentry. In this latter respect, it is more akin to the 19th

century cenotaphs north and east of Galway city (including the complex near

Cong) which honour society elite (Robinson 1995, 117).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cooke, Thomas L.

(1842-43) . Autumnal Rambles about New Quay, County Clare.

Galway -

Galway

Vindicator.

Coffey, T.

(1995). Field Notes – Rock Art and Related Rock Scribings in the County Clare. The Other Clare

19. Ennis - Shannon

Archaeological and Historical Society.

Beresford Massey, E.H. (1902) Association for the Preservation of the Memorials

of the Dead Ireland. Vol V (2).

Tunney, M. (2019). www.archaeology.ie

Dublin - Ordnance Survey Ireland.

Comber, M. (ed.) The Antiquities of County Clare. Ordnance Survey Letters 1839 O’Donovan,

J. and Curry E.

Ennis – Clasp Press.

Robinson, T. (1995). Stones of Aran

Labyrinth

. New York - New York Review of Books.

WILLIAMSON AND BYRNE

ROCK SCRIBINGS

INTRODUCTION

There are

three stones within the fabric of the well house with scribings on them. Two of

the stones are approx. 0.6m by 0.3m whilst the third one is approx. 0.15m by

0.12m. Discussion of the etchings has

heretofore been limited to a short piece by Coffey in the mid-'90s(Coffey 1995, 16). Moreover, in an exciting development, previously invisible etching detail has now come to light.

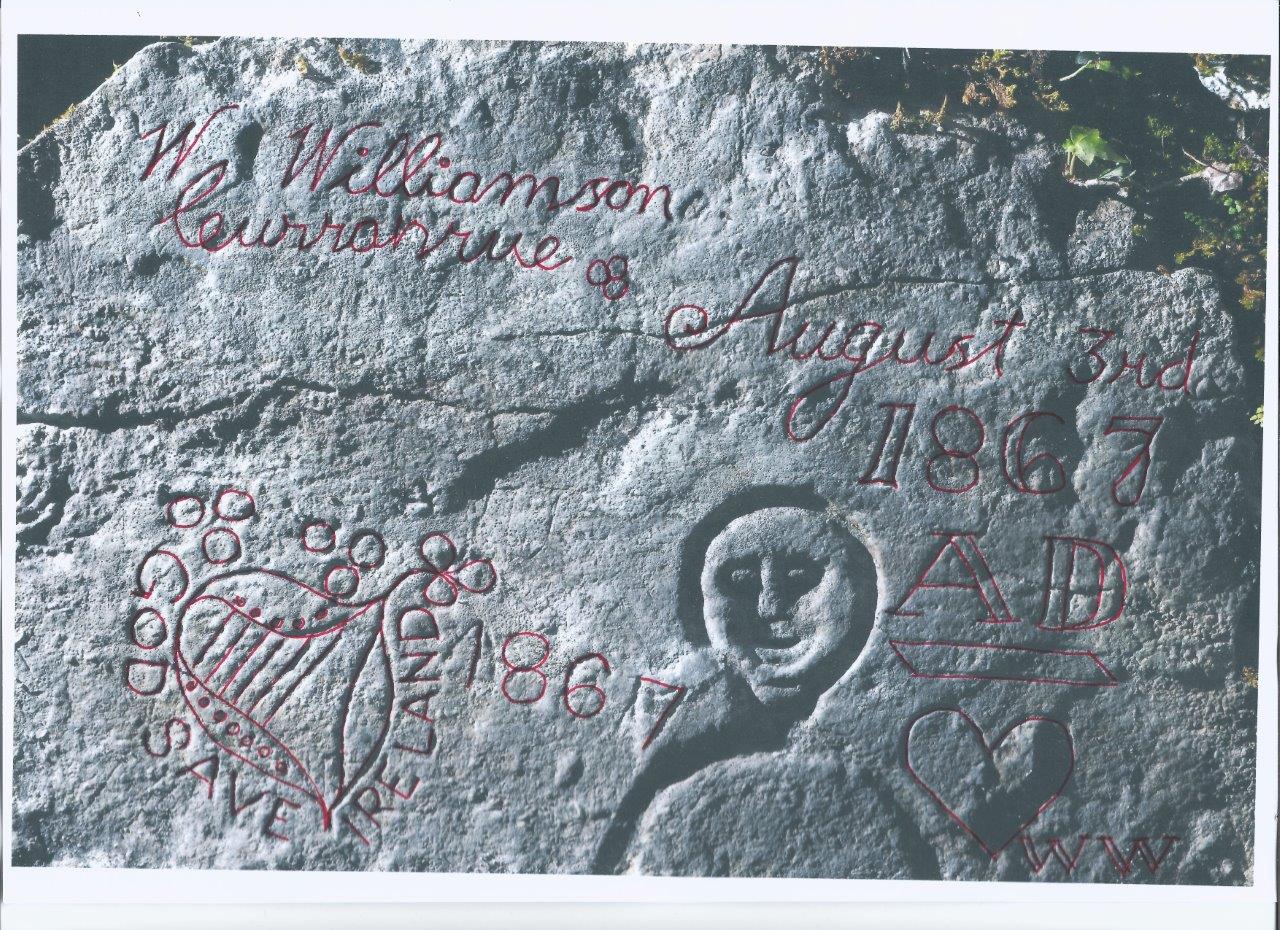

WILLIAMSON

The lower of

the two larger stones is the “sun face stone” which was moved from the

cenotaph. The main inscription subsequently added to the stone is “

W. Williamson, Curranrue August 3rd 1867 AD”.

(Curranrue is now spelt Corranroo). The wording is etched in a very

neatly written copperplate script with double strokes on “1867” and “AD”.

Williamson’s initials (“WW”) are to be seen in the bottom right corner below a

heart. The motto “God Save Ireland” encircles a harp in the bottom left corner.

A shamrock is part of the minor decoration outside the circle. “1867” is etched

again to the right of harp and motto.

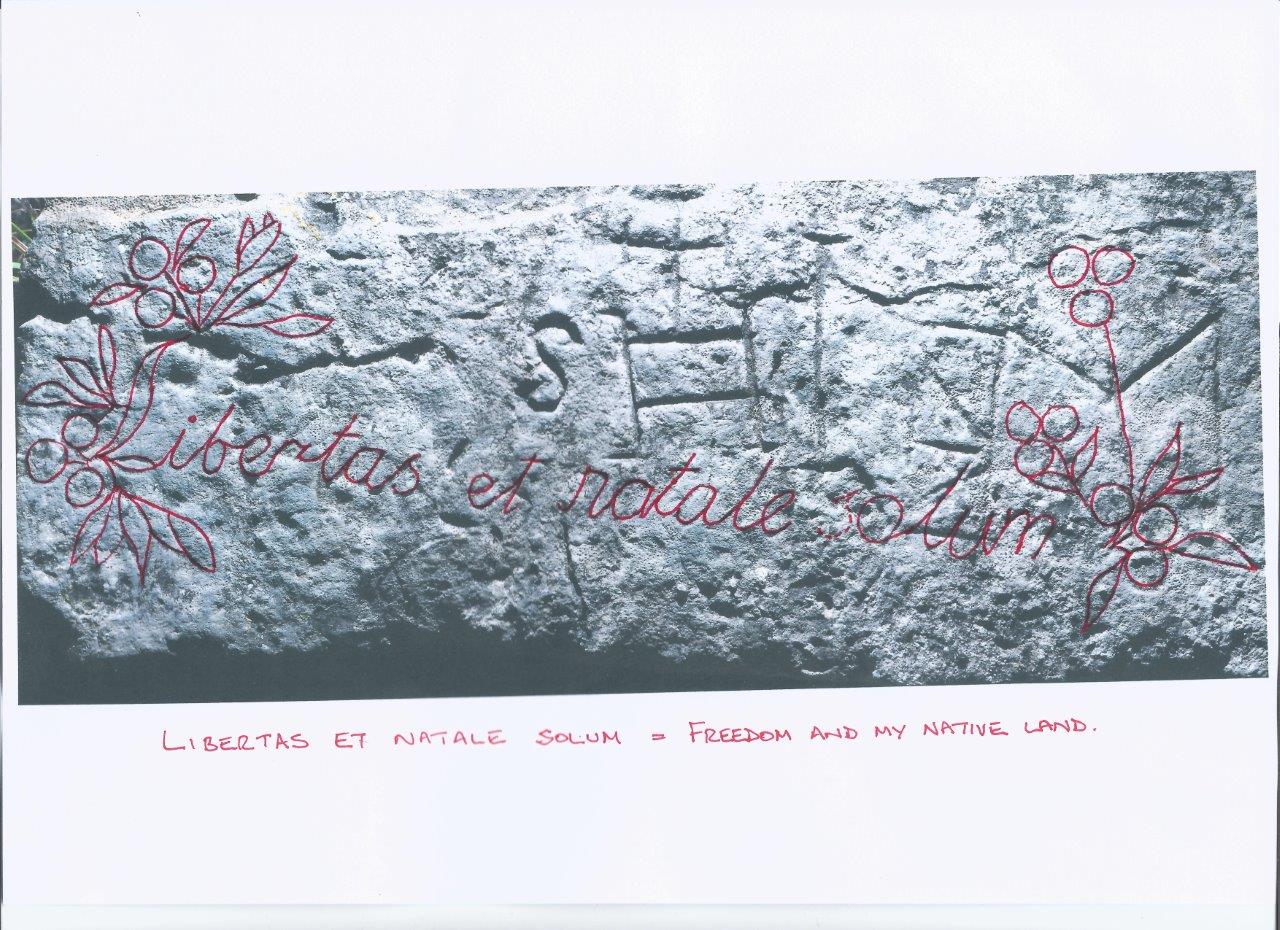

The top stone has some fairly ornate flowers on the left leading into more copper plate script. The first part of the script is a flower-illuminated "L" of the word "Libertas". The "L" also has the distinctive feature of double strokes which is evident in the lower stone. There are more flowers to the right of the script. The text is in Latin and reads – “Libertas et Natale Solum”, which translates as Freedom and My Native Land.

As both stones express nationhood sentiment and feature very neat copperplate script with stylistic similarities, one can conclude that the entirety is the work of Williamson.

Williamson’s rock scribing would have been quite time-consuming which suggests that he attached a lot of importance to it. The knowledge of Latin and the tidy handwriting style would indicate that the author was an educated person. Furthermore, he or she was obviously an ardent nationalist. Apart from the nationhood sentiment in Latin, “God Save Ireland” was a cry in vogue amongst separatists in the late 19th century as autonomy was sought from Great Britain.

Edward O’ Meagher Condon was one of five

Fenians found guilty of murder in Manchester on November 1st 1867. Three of the five Fenians, known as the Manchester Martyrs, were hung. O’Meagher Condon was

reprieved on account of his U.S.citizenship. His speech from the dock ended with the cry “God Save Ireland”. The phrase subsequently

became widespread amongst the Irish worldwide and the refrain of a famous ballad (1994

Curtis, 73). However, the fact that the words were etched in stone in North

Clare three months prior to O’Meagher Condon’s famous cry would

suggest that “God Save Ireland” had already been in usage

prior to the famous dock speech.

Curranrue is the plain and bay which lie

just below the well to the north east. “Curranrue

Bay, in common with everything in this neighbourhood, owes much to the

enterprising spirit of its owner” (Cooke 1842-43).The owner was Burton Bindon and

he spent of much of the year living in the village of Curranrue (no longer

extant). It has not been possible to trace

Williamson of Curranrue. Could the name be an alias for somebody who wished to

publicly express his/her political sentiments in an anonymous fashion in

turbulent times?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coffey, T. (1995). Field Notes – Rock Art and Related Rock

Scribings in the County Clare. The Other

Clare

19. Ennis - Shannon Archaeological and Historical Society.

Curtis, L. (1994). The Cause of Ireland.

Belfast - Beyond the Pale Publications.

Cooke, Thomas L. (1842-43) . Autumnal

Rambles about New Quay, County Clare.

Galway -

Galway

Vindicator.

BYRNE

The third etched

stone measures 0.15 m by 0.12m approx. This etching is a far less ornate affair than that of Williamson. It is devoid of artwork and the lettering is plain. The inscription reads – “M.

Byrne RIP AD 1916 Kinvara”. The words “M.

Byrne R.I.P.” have been previously documented. “1916” and “Kinvara” have also

been recorded though they were not associated with Byrne. The “A.D.” has not

heretofore been recorded at all (Coffey 1995, 16).

The Kinavra connection is not surprising given that the well was popular in the past with Kinvara folk. “The two holy wells that are best known are St. Patrick’s and St. Colman’s. St. Patrick’s well is situated about three and a half miles from Kinvara”. (Irish Folklore Commission (IFC), 0049 p. 0169).

The only Byrnes recorded in Kinvara in the period around 1916 lived in Rineen, Doorus. In the 1901 census the surname is given as Beirne. The household is Pat 50 and Mary 45 plus children Michael 17, Patrick 12, Mary 10, Bridget 8, Ellen 5. Pat and Mary’s ages are almost certainly incorrect and should read 60 and 55 respectively.

In the 1911 census the family name is registered as Byrne. (The surname varies

between Byrne and Beirne in census and register of marriage and deaths). The

household in 1911 is Pat 70, Mary

65, Patrick 20 and Ellen 12. Michael,

Mary and Bridget are no longer

registered as part of household.

The father Pat was from Roscommon. He and Mary married there in 1864.

Mary died at 70 years of age in Carrick on Shannon on 9th June 1916. A small

part of Carrick-on-Shannon is in County Roscommon. Evidently, Pat and Mary

moved there in later life. Mary is described as a farmer’s wife on her death

certificate and she pre-deceased Pat.

One of the three M. Byrnes from Doorus is memorialised

at the well. It is either mother Mary, son Michael or daughter Mary. We have no

record of children Michael and Mary subsequent to census 1901 whereas mother

Mary’s year of death coincides with that in the rock scribing “M.Byrne RIP AD

1916 Kinvara”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coffey, T. (1995). Field Notes – Rock Art and Related Rock Scribings in the

County Clare. The Other Clare

19.

Ennis - Shannon Archaeological and Historical Society.

COMESHILL

There is one further memorial on

site. It consists of a small sheet of zinc

or similar about 0.125m by 0.125m. The edges of the plate have been folded back

and cemented on to the cliff face. The wording is - “In memory of Matthew Comeshill

who died in Ireland August 13th 1958” and it is hand-engraved in copperplate script.The plate is located at head

height just before one steps down in to the well.

Mr Comeshill may have been on a visit to Ireland when he passed away. Subsequently, family or friends must have decided to mark his passing with a memorial. This site may have been chosen as Comeshill himself had considered it outstanding - with its spiritual energy and stunning views.

What is beyond doubt is that the plate is further evidence of the rich and curious tradition of memorialisation at St Patrick’s, Rossalia.

CREDIT

All photographs by Nick Geh.