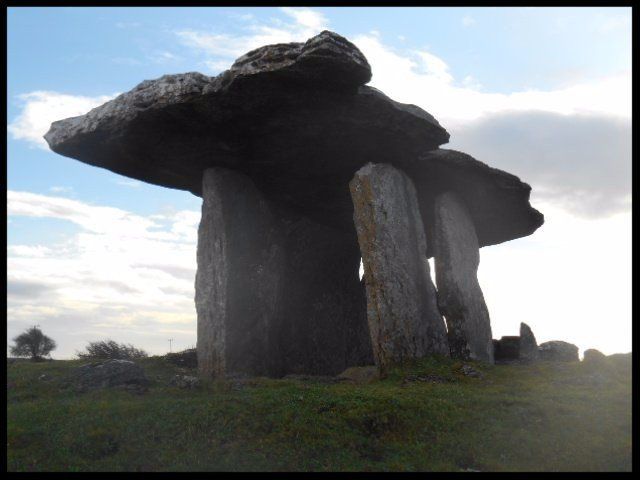

Ballycasheen Portal Tomb, Killinaboy.

“Sometimes one really does

have to wonder why some monuments get signposted and some don't. Of the many

spectacular tombs scattered around the Burren this has to be one of the worst!

It is terribly neglected and very overgrown. There is so little of the tomb to

see, just a few slabs that were once the chamber”.

Description of

Ballycasheen portal tomb by www.megalithomania.com

in 2002

INTRODUCTION

It is December 2017 and I train my binoculars through my kitchen window onto a field a couple of kilometres to the north. I can see for the first time Ballycasheen ( Baile Chaisín Caisin’s place) portal tomb. The monument had been covered with blackthorn and bramble for decades. However, all changed on the 25th of November this year when a team of volunteers under the expert guidance of prehistoric archaeologist Ros O’Maolduin cut away the scrub in and around the monument.

The volunteer team is the Burren Conservation Volunteers (B.C.V). B.C.V. were set up in 2010 by the Burrenbeo Trust to answer a need for active conservation in the region. The Trust itself is a landscape charity. The Ballycasheen day was a hugely successful exercise in monument management.

B.CV. thus returned Ballycasheen in part to its former glory. I say “in part” as unfortunately the tomb is in a collapsed state with the two capstones no longer sitting spectacularly on the lateral standing stones. As a result Ballycasheen does not enjoy the “drama” of the sharply-tilted roof of the only other portal tomb in the Burren, Poulnabrone. The father of Burren archaeology, T.J. Westropp, lyrically referred to Poulnabrone as being noteworthy for ”the airy poise of its great top slab”.

Reference

“Archaeology of the Burren.

Prehistoric Forts and Dolmens in North Clare”. T.J. Westropp. Clasp Press.

1999.

MEGALITHIC TOMBS

There are 3 types of

megalithic tomb associated with the Early Neolithic period in Ireland (6,000 to

5,000 years ago). They are passage, court and portal tombs. Pioneer farmers

reached the Burren and Ireland about 6,000 years ago. They brought with them a

new mortuary tradition – interring their special dead in big stone structures.

These megaliths are also very loud statements of territory. Perhaps most

importantly of all, they served as temples. The living frequented the

structures in order to commune with the otherworld.

The last in the suite of megalithic tombs is the wedge tomb, dating to the Late

Neolithic period (5.000 to 4,000 years ago).

LANDSCAPE

Poulnabrone may have been a tribal boundary at the most northerly point of the

Burren in Neolithic

times.

The tomb is located on a limestone pavement plateau in the uplands. Carleton

Jones argues that the location may have denoted a frontier point with

Ballyvaughan valley and its virgin oak woods below to the north.

Two of the eight Early Neolithic tombs so far discovered in the Burren are located between the river Fergus and Roughan Hill. They are the Ballycasheen portal tomb and a court tomb which lies 250 metres south-east of it. So in its turn, the Ballycasheen portal may

well have been built at a critical southern entry point to the region -

situated as it is between the river and the hill.

This gap between hill and river seems to have also been a sought-after location of

buildings of the élite in later, historical times – witness the Early Medieval (431 to 1169 A.D.) monastic

site of Kilnaboy ; the ring fort of Caher Mór which may also date largely from

the Early Medieval period and the Medieval (late 12th century - early 16th century A.D.) Leamaneh Castle entrance.

Refrences

“The Burren and the Aran Islands Exploring The

Archaeology” Carleton Jones. The Collins Press. 2004.

“Temples of Stone. Exploring the Megalithic Tombs of Ireland” Carleton Jones.

The Heritage Council. 2007.

FARMING

The economic and political

power of the Neolithic communities was derived from farming - the most radical

ecological experiment known to mankind. The pioneer farmers in the Burren opted

to exploit the limestone pavement/thin

soil areas (mostly in the uplands) rather than the thick glacial deposits over

limestone (largely in the valleys). They chose the former as the tree complex

of hazel and Scots pine was easier to cut with their polished stone axes. (The

valleys had a dense cover of oak wood).

The megalithic tombs are thus concentrated in the prehistoric upland

farming landscape.

The pressure on the upland landscape of slash-and-burn and farming was

heightened 3,000 years ago with a change to a wetter and windier climate. The

result was a dramatic loss of soil and the exposure of more pavement in the

hills.

The rocky hills were no longer viable for all year round farming due to dearth

of soil. Economic activity and human settlement switched to the valleys.as the

oak was removed. The overwhelming concentration of Early Medieval (400 A.D. to

1100 A.D.) monastic sites in the Burren valleys would suggest that by this

period at the latest, most of human settlement had moved from uplands to

lowlands.

The tradition has been in decline over the last 50 years or so with the inevitable ecological succession of scrub. Scrub is an enemy of archaeology and that is why the BCV opted to remove it in Ballycasheen.

WHAT MAY LIE BENEATH

There are just less than 100 megalithic tombs recorded in the Burren and Poulnabrone is one of the few have been excavated. We can surmise to an extent from the Poulnabrone findings what may lie below the earth at the Ballycasheen portal.

It was Ann Lynch and a team of National Monument archaeologists who excavated in 1996-98. They found the remains of 33 individuals. Some of the remains were charred and some unburned. The team also found bones of wild and domestic animals as well as grave goods including stone and bone artefacts and a small polished stone axe.

Ann Lynch concluded from examination of the human bones that the interred had had short, physical and violent lives. The date range of the bones is about 600 years – 3800 B.C. to 3200 B.C. approximately – extremely selective burial of the dead.

Reference

“

Poulnabrone: An Early Neolithic Portal Tomb in Ireland”.

Ann Lynch. Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. 2014.

MYTHOLOGY and FOLKLORE

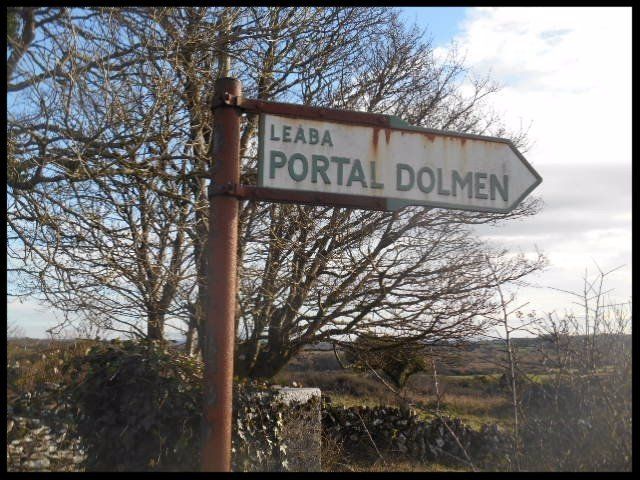

The Ballycasheen sign post on the road refers to the tomb in Gaelic as “Leaba”. There are still a small number of elderly people in the parish of Killinaboy who refer to certain megalithic tombs as “leabas”.

Diarmaid and Gráinne are two parts of a love triangle in a tale from the Fenian Cycle of Mythology. Many Stone Age tombs with flat roofs around Ireland were believed to be used as overnight refuges by the couple in order to hide from the pursuing warrior Fionn Mac Cumhaill. These monuments were known as Leaba Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne – Diarmaid and Gráinne’s bed.

W.G. Wood Martin points out that the monuments were also linked with “aphrodisiac customs”. Martin recounts Hely Dutton’s experience related to his search for the Ballycashen monument in 1808. Dutton was visiting the monument as part of his work for the publication “A Statistical Survey of County Clare” commissioned by the R.D.S.

When Dutton asked a couple of

local women directions, they indulged in an animated chat together in Gaelic.

The younger one eventually undertook to accompany Dutton to the tomb on the

understanding that he was a stranger to the area (not local) and that he would

give her his name.

Dutton became impatient and rode off. He subsequently told another local woman of his encounter and her comment was 'No wonder for them, for it was the custom that if she went with a stranger to Diarmaid and Gráinne's bed, she was certainly to grant him everything he asked.'

The “leabas” were also centres of fertility ritual. Wood Martin comments that “No doubt but that from Pagan times comes the widespread notion that these "beds" were efficacious in cases of barrenness. Hely Dutton remarked that if a woman were infertile, a visit with her husband to Diarmaid and Gráinne’s bed would cure her.

References

“A Statistical Survey of County Clare” Hely Dutton, 1808.

“Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland ; A Folklore Sketch ; A Handbook of

Irish Pre-Christian Traditions” W. G. Wood-Martin, 1902.

TOURISM

The original structures of Poulnabrone and Ballycasheen each had two capstones. The only capstone surviving on lateral stones now is the one at Poulnabrone.

This massive sloping capstone explains in part why Poulnabrone attracts up to 200,000 visitors per annum, (electronic counter on site). The antiquity of the monument and the accessibility of the site are the other main reasons why Poulnabrone is the most visited tourist site in the Burren. (The site is roadside on the R480, a major arterial route through the region).

From my own observations, I would find it hard to imagine Ballycasheen having any more than a couple of hundred visitors per annum. The monument’s tiny visitor numbers are explained in part by its location on a minor road ; its occlusion by scrub for decades ; its collapsed state and the displacement of its tilted roof.

EXCAVATION

Excavation of archaeological monuments in the Republic of Ireland can only be acted on with an excavation license. Under the National Monuments Acts, ownership of any archaeological object with no known owner is vested in the State. This means in effect that all archaeological findings must be transferred permanently to the National Museum of Ireland after examination. Thus, Poulnabrone is a funerary monument devoid of its dead - an empty tomb.

Only a minority of archaeological finds are actually exhibited in the National Museum’s public site in Kildare St in Dublin. The majority of objects are held in a facility in Swords, North County Dublin. The National Museum of Ireland – Central Resource Collection is in an industrial unit which was formerly the home of a Motorola electronics assembly plant.The 18,000 square metre building is the size of two football fields and houses several million archaeological objects.

There are no plans currently to excavate the Ballycasheen tomb. As only a small fraction of the region’s archaeological monuments has ever been excavated, the fate of our ancestors at Ballycasheen may be to rest in peace in their house of death.

CONCLUSION

Ballycasheen is one of only two portal tombs in the Burren. Moreover, it is one of the few Early Neolithic tombs which has been discovered in the region. It is a monument of real cultural significance in the Burren’s prehistoric landscape.

Ballycaseheen has had the good fortune to be “unveiled” again by conservationists. The second coming of the tomb means that a visit to the site is now a gem of a Burren experience. Its luck could hold out as it will never be overwhelmed by visitors and may also elude the excavators.

The turning of the year was an occasion of real spiritual significance to prehistoric farming communities. It marked the start of the journey from darkness in to light. The Ballycasheen site is a very soulful place to be on a sunny mid-winter’s day. Enjoy the holidays and the turning of the year.